Loving Their Differences

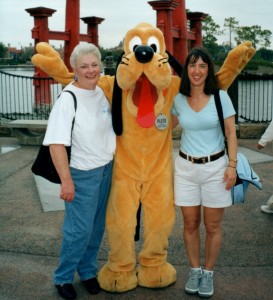

BeaAnn Braun: 60, married, 2 children

Best friend of 40 years: Melanie Scott, divorced, died ... complications after emergency surgery for a bowel obstruction in 2012 at age 58

“It was like no other relationship I have had.”

How did you meet?

I met Melanie during our freshman year at Northwest College in Powell, Wyoming. I was 17 and she was 18 and we lived in the same dorm. I was from Indiana and had never been west of the Mississippi. Melanie had been living in Buffalo, Wyoming, not far from the college. She was very articulate, intelligent and funny. We were often on the same schedule and would walk to meals together. And we were both night owls and got to be really good friends the second semester of our freshman year.

Melanie was very genuine, direct, insightful and wise. She laughed easily. She had experiences that I did not have and I had stabilities that she didn’t feel she always had. We appreciated how life had gotten us to the same point very differently. Her dad was a civil engineer and in second grade she moved to Lahore, Pakistan and lived there through the ninth grade. I had gone to 12 years of parochial school. She knew that there were many ways to live and many ways of looking at religion. I remember once I said, “You know, I think I realize that things that are right for me are not necessarily the right choice for everyone.” She started dancing around and said, “Oh hallelujah, I didn’t think you’d ever get there.” And she found some kind of comfort in my outlook. During our sophomore year, she converted to Catholicism. I was her sponsor— though I was a little uncomfortable with it. I didn’t want to be responsible for her converting.

What was the friendship like?

I was in sciences and she was a communications major. She was on the debate team for our college and she competed nationally. Our interests were surprisingly different. I was always doing something active and she would rather read a book. But we enjoyed each other’s personality and we weren’t afraid to be totally honest with each other.

I remember one night we were walking the campus and we stopped at the swings on the playground and she said, “Do you ever wonder who you’re going to marry?” I said sure and she said she did too. I said, “Whoever they are, they’re out there right now.” She loved that idea. She just really enjoyed that thought and I saw her visibly relax.

Together we were anchors for other friends too. We were kind of a go to place on campus. It was like there was Melanie and there was BeaAnn and then there was the two of us. She was the dorm president in freshman year and sophomore year she was president of the student body. I was an RA. We lived in the honor dorm, which was half male and female – in 1972 that was a new thing – and it was a very, very close-knit community. You were allowed to paint your room and you were allowed to bring in your own furniture. As the student body president, she had a private room and as the RA for the dorm, I had one as well. They were right next door to each other, so we made one room the bedroom and one the living room, which became a gathering place. We often came home from classes and found friends waiting for us. It was a place to be and it was something that the two of us created.

Sometimes we liked to engage in false, created conversations in public to get other people’s attention. One time in college we drove to a diner and started a conversation about being kicked out of the dorm, which was bogus. But we did it just to get attention and see how people would react.

Many years later, it was in Chicago in the late 70s, Melanie came from Wyoming for a visit. We got to the Chicago Museum of Natural History for the King Tut exhibit and the line was wrapped around the building. They were giving tickets according to when you came in and we knew that we were not going to get in that day and it was the only day she had. She said, “We have to see how to get up in the line.” So we casually scooted up, but people got mad. She said, “Our plan is all wrong. We have to go up far enough in the line that the people around us aren’t worried about getting in. Then they won’t object as much.” I said, “Okay.” Then she said we have to make it so the people want us there. She said, “Let’s sign or start a signing conversation because people like to watch people sign.” I said, “But you sign and I don’t.” So she said, “That’s all right, we’ll figure it out.” She did most of the signing; I would nod or gesture and people were enjoying watching the conversation. When the line moved up, we just went in with everyone and got tickets. It was a good thing we did because the tickets that we got at 9:00 in the morning were for 3:00 in the afternoon. Had we not moved up she won’t have seen the exhibit because she flew home the next day.

One of Melanie’s early jobs was directing the preschool for children with disabilities in the town where we went to school. After college, I went back home and found a job where I met my husband. She and I never again lived in the same town, but we talked on the phone a lot and had conversations that lasted hours. We visited each other often.

She was in my wedding and it was a little uncomfortable because I knew she wanted so badly to meet somebody. She gave me something out of her hope chest and I knew the sentiment of it, but I didn’t want it to be a giving up on her part.

We talked a lot when she was doing her masters because she was so afraid of taking the math class. She would cry on the phone and I’d get her through it and give her some pep talks. I’d send her little writings to help her when things got tough. There were some signs when we were in college that I know now were the beginning of depression, but I didn’t know what it was then. She would curl up with a book and not talk and not interact. I would say, “You are not allowed to withdraw.” She told me later that helped her not become a hermit. She remembered me saying, “You’re not allowed to behave like this when you have others around you who care.” But she did have trouble with depression; it became more apparent as we got older. She was sometimes able to talk about it. She told me how her doctor would say, “Get out and go for a walk.” And she would say, “That’s the problem. I can’t get out and go for a walk.” She tried a lot of different things.

When she was in her late 30s she married Al, her debate coach. We had the wedding back at the library of the campus where we had gone to school. She loved books, words, language, reading and the library was the perfect place for her and Al to be married. She moved from Florida to be with him where he was living then in Winston-Salem. She liked the academic environment very much, but after about seven years she wasn’t happy. She told me that he was emotionally unavailable, but Al would tell me that she didn’t like him anymore. Like most divorces, there are two stories. She moved back to Florida to be by her sister and that’s where she lived for the last 18 years of her life.

My life was changing too. At 50, I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. It’s a high maintenance condition to have, but 10 years later, I’m still doing well with it. I remember one of our last conversations. She said, “So you’re okay?” I said, “Yeah, I wish my body worked a little better, but I’m okay.” And she said, “Wow. I wish my brain worked better, but I’m okay.”

Another thing that was rough was when her mom passed away. She called to tell me and I said, “Mel, my mom died a year ago and I couldn’t get in touch with you.” She said, “I should have let you know that my phone number changed.” She was really surprised and it struck her that her reclusiveness, that was really prompted by the depression, had affected us. She said, “Oh my gosh! I can’t believe that I did that.” She felt terrible and started to judge herself for not being there for me. And I said, “It’s OK. You know I’m here.” Then we talked about her mom and how hard it was for her to lose her.

We did start to talk on the phone more after that. There was a closeness there that never went away even if there was a ripple of things that weren’t going right; the bond was still there.

I think I helped Melanie be grounded and, conversely, she taught me how to think bigger and wider. She also helped me learn to trust myself and to trust my interpretation of an event or a situation. We’d get on the phone and it was sort of a life playback. We would say: this is where I am now and this is what happened; and what do you think about that and how should I handle it; and no, you did fine or how about try this, try this direction; or just looking at your own life through another person’s lens and like, yes, you interpreted that right or how about this angle on it. It was like no other relationship I have had. We never had cross words, but she pulled back at times because of the depression. That’s where we were when she passed.

Describe how the friendship ended.

Her sister called me and told me that Melanie had died from complications after emergency surgery for a bowel obstruction. It is strange, but I have an awareness of a conversation that I had with her after I knew she had died. I talked to her. I said, “Hey, what happened?” And she said, “Well, it was like this, I had this pain.” And she told me the story of her getting sick and needing to go to the hospital and then what happened. I can hear the conversation, and it’s very much her personality, even though I know it didn’t happen. I don’t remember dreaming it. I don’t remember waking up having dreamt it. It just became a part of my memory of her.

How did you cope with her loss?

I wish I had been there for her. It’s really hard that I wasn’t there. Mel was cremated and her brother-in-law from Florida came back to the campus where we went to school together and we gathered people that were friends of ours and spread her ashes in the flowerbeds at the library.

I talk to her ex-husband Al sometimes and she had another dear friend from college who I talked to a number of times right after her death. The thing that is comforting to me is the conversation that never took place or maybe it did take place in another realm because the conversation is very clear. I think when that conversation with Mel happens she is reaching out somehow. I think when we all die, we are all going to have flatter foreheads from hitting our forehead and going, “Oh I get it.” I don’t think we understand it, but I’m quite sure there is another dimension there somehow that I know I don’t understand but I respect its existence and I think she’s there.

Before Friendship Dialogues was a gleam in founder Ellen Pearlman’s eyes, a group of over two dozen women answered her online plea for women who had lost a female best friend. Ellen is eternally grateful to all the women, including BeaAnn, for opening their hearts to her and sharing their personal stories of love and loss. It was through this process that the seeds for Friendship Dialogues were planted. Thank you!